Rotational Grazing: What It Is and Why It Matters

When most people think of dairy cows, they imagine Holsteins grazing on grassy, rolling hills or in wide, open pastures. Though some dairy farms may have cows living this lifestyle, most cows are not so lucky.

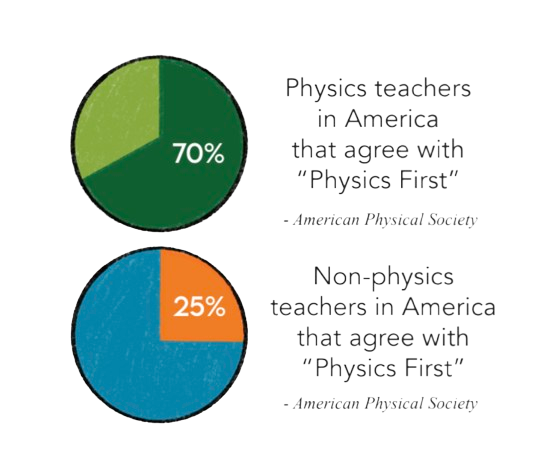

Farms classified as potential CAFOs, or concentrated animal feeding operations, are farms that have over 1,000 EPA animal units (700 mature dairy cows). According to the USDA, in 1997 about 9% of all livestock-owning farms were large “commercial farms,” but made up around 31% of all CAFOs.

The appeal of CAFOs is their potential to provide cheap and accessible food to millions of people, but there are many drawbacks. Perhaps the largest drawback of all is the environmental impact of their manure production.

According to the CDC, 800,000 pigs produce 1.6 million tons of sanitary waste per year. This would equal every person currently living in the city of Philadelphia producing just over one ton of feces per year (2,000 pounds) or about 5.5 pounds daily. If CAFOs are placed close together, these large amounts of manure can lead to groundwater contamination and pathogenic spread, along with a high volume of methane emissions.

However, there is an alternative to environmentally detrimental CAFOs: rotational grazing.

Rotational grazing is a method in which cattle are allowed to graze in a series of small pastures, with their manure fertilizing the grass as they move on to eat the next pasture in the series. This method ensures that when they return back to a pasture they have eaten, the grass will have grown long enough for them to eat it without overgrazing and killing it.

For example, a herd of dairy cattle might graze in Pasture 1 on May 12th, and will go on to graze in Pastures 2-15 in the two weeks after. Then, on May 25, the herd will return to Pasture 1 to long, healthy grass and will eat once more.

With the right grass type, this cycle has the potential to continue onward indefinitely. For some first-hand information, I interviewed Pete Stickney, the Farm Manager at The Putney School in Putney, Vermont.

Putney has a herd of about 40 cows at any given time, usually made up of about 30 active milk cows and ten other cows (heifers, beef cattle, etc.), and roughly 20 acres of actively managed pasture land. There, the cows are out at pasture all day except for their two daily milkings in the summer, and in the barnyard for about six hours daily in the winter.

In the spring, summer, and early fall Putney’s cows eat mostly orchard grass and dry hay, and in the winter they eat mostly round-baled fermented hay. Their diet of pasture grass increases the quality of cows’ milk, making it taste sweeter and giving it a more golden color. Rotational grazing not only allows Putney cows to produce incredibly high-quality milk at a relatively low cost, but also reduces the amount of labor involved in pasture management.

When discussing taking the cows out to pasture, Mr. Stickney said, “…the good thing about rotational grazing is [that] those paddocks the cows are going to haven’t had any manure or fertilizer spread there in 20 years now…the plants are there, the nutrition is there, all we need is a little rain.”

Small dairy farms practicing rotational grazing can provide wonderful milk at a low cost to consumers, cows, and the environment. They generally have fewer waste issues than CAFOs, and can be thriving family businesses that continue for generations.

However, for them to replace CAFOs would require a massive decentralization of the American dairy industry and food systems as a whole. It would also mean that more people in areas ideal for raising cattle would need to take on agriculture as a profession. Still, rotational grazing is a viable, environmentally-friendly alternative to large-scale dairy farming that can produce happier cows and happier consumers along the way.

Georgia Jane is the Features editor for the Hourglass and has written for the paper since 9th grade. She spends her time outside of school rowing, listening...