Choosing Facts Over Falsehoods

The prevalence of misinformation in the media, and our responsibility to discern between real and fake.

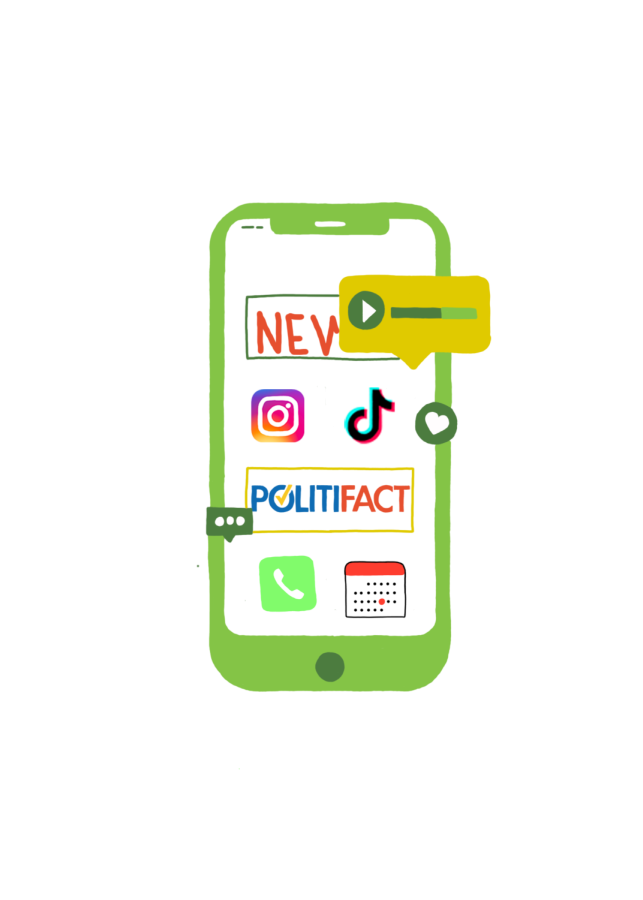

A quick scroll through PolitiFact—a fact-checking website that evaluates the accuracy of online posts, articles, quotes from significant figures, and more—reveals dozens of recent claims of increasing absurdity.

For instance, one string of posts suggested that President Biden was not actually present at the State of the Union, but rather someone else in a “Biden mask” delivered his speech for him. Another claimed that NASA has stopped exploring the ocean out of fear of something they discovered in the depths. One video even claimed that the United States “no longer exists” because Biden “signed away our sovereignty as a nation” in the Declaration of North America.

It may seem obvious that all of these claims are blatantly false, but all three have amassed thousands of views. What else do these false statements have in common? They were all initially posted on one social media platform—in these cases, Instagram or Facebook—then virally spread to other platforms.

These are just a few examples of “fake news.” This phenomenon is nothing new, of course, but it has been significantly exacerbated by the birth of the internet. As social media platforms grow, their ability to rapidly circulate information does, too.

Some social media platforms have implemented measures to combat misinformation. For example, Instagram labels information that has been flagged as false by third-party fact-checkers and removes it from the Explore page, although not from the platform. Facebook has a similar policy, and in recent years, has escalated efforts to remove fake accounts from the platform. Despite these policies, fake news persists.

“Don’t believe everything you read online” is a repetitive saying by now. Most upper schoolers have been navigating the internet and social media since we were children, and many of us may believe we’ve learned how to tell the difference between facts and fiction.

But sometimes, it’s harder than it seems to recognize what’s real, and the evidence shows we’re not as good at discerning reality as we think. In fact, recent research from Science showed that false news was retweeted and traveled farther more often than true news on Twitter.

This fake news often appears in other forms of highly consumable content: seemingly-innocuous memes, TikToks, and carousel posts that take only a few seconds to scan and share. When these posts and videos are edited, it’s even harder to tell what’s real.

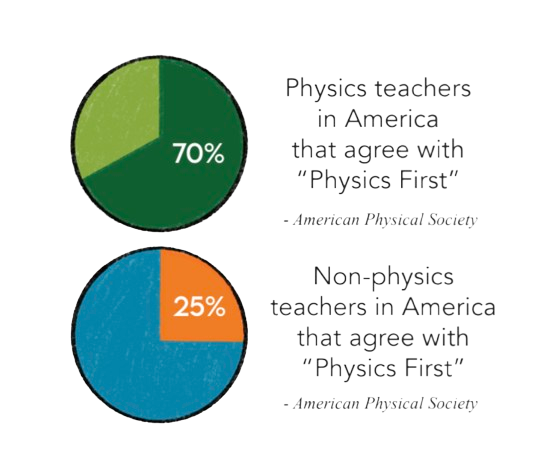

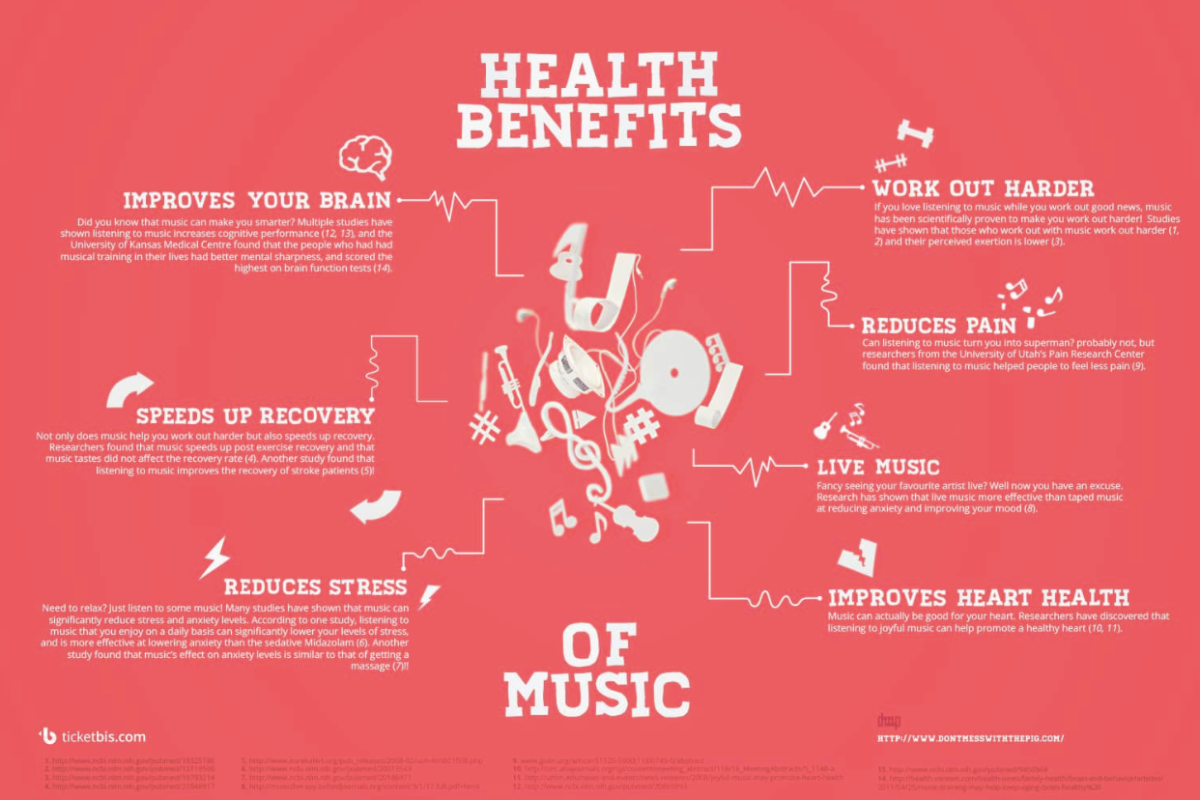

Moreover, the “truth” isn’t always black and white– biased reporting can oftentimes obscure objectively accurate facts. This problem has come into sharper focus in the field of science writing: statistics can be easily skewed, “scientific experts” are not always vetted, and without context, “fact” can easily be twisted into fictitious clickbait. We hope that this issue’s centerfold will serve as an example of accurate science reporting– with the intention of being informative, rather than inflammatory.

The next time a dubious news story pops up on your feed, remember that there are lots of resources available to you to verify the information before sharing: The MediaWise Teen Fact-Checking Network or the News Literacy Project’s RumorGuard are great places to start.

Unfortunately, misinformation will probably continue spreading at an exponential rate. We encourage everyone in the Baldwin community to make an active choice: to spread the truth and renounce falsehoods.

https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/18/business/tiktok-search-engine-misinformation/index.html