What Fireflies Tell Us About Pollution

Picture yourself walking through a park on a quiet summer evening. The moon and the stars are completely sheltered from view–there are no cars, no lamps, and no bright windows from houses. Darkness. All of a sudden, you catch a glimpse of tiny luminescence out of the corner of your eyes, like a sparkle popping in the air, a nameless fallen star. What was that? It could be nothing else but a firefly.

Fireflies are perhaps one of the most charismatic kinds of insects in the world. They are famous for their distinctive bioluminescent lights, which play an important role in their mating practices.

In North America, Photinus fireflies are the most common kind. They emerge and fly around in the spring and summer.

The quintessential scene of fireflies on a summer evening was described by the American poet Robert Frost in his 1930 poem “Fireflies in the Garden.” He compared the fireflies with the stars: “Here come real stars to fill the upper skies,/And here on earth come emulating flies.”

While stars can be billions of years old, fireflies only live for about four weeks. Despite this, they share one similarity—they are both vanishing due to human pollution.

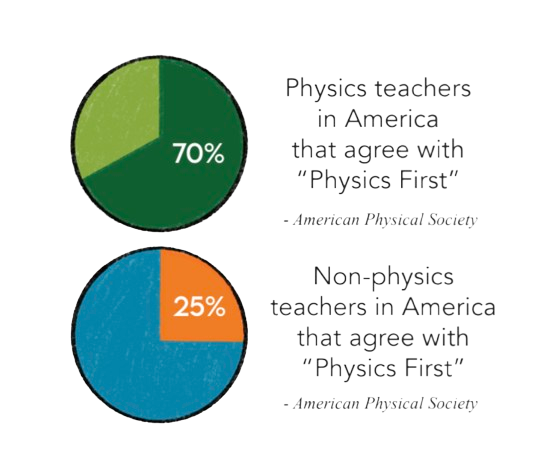

According to BioScience, fireflies’ reproduction rates are decreasing due to light pollution, which outshines their mating signals. Out of ten possible factors, artificial light is, on average, the second most significant threat to the long-term survival of fireflies around the world.

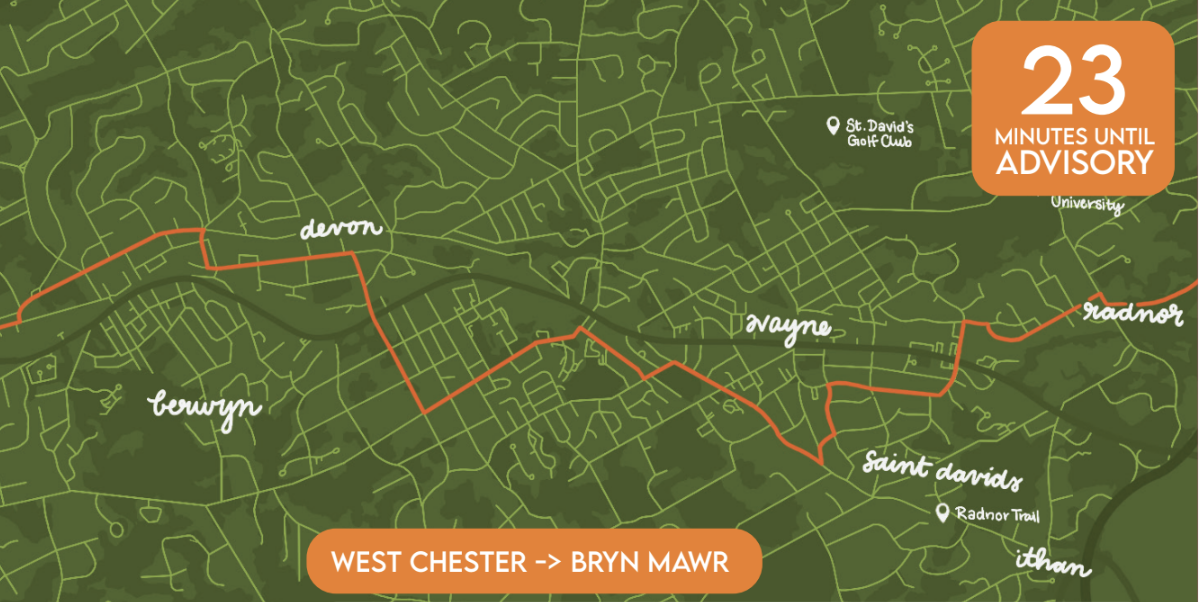

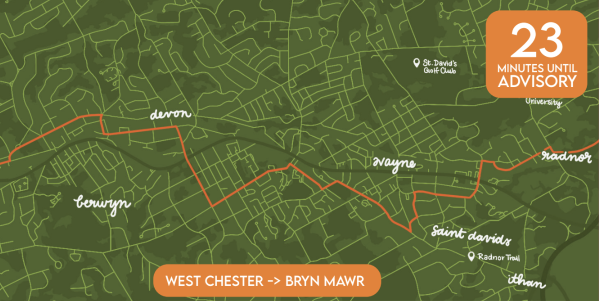

Artificial light at night, or ALAN, includes direct lighting like street lamps, sports arenas, and commercial signage. There is also a phenomenon called skyglow, which is when the upward light from the city is reflected in the air and causes the entire sky to light up unnaturally.

It is estimated that more than 23% of the Earth’s surface is illuminated artificially. Such bright nights are detrimental to fireflies because they rely on their bioluminescent signals to locate mates, and ALAN renders them unable to do so.

However, it is impractical to get rid of ALAN altogether—things like streetlights and road signs are necessary for the world we live in. Some scientists, hoping to find a compromise, investigated if certain colors of light affect the fireflies less.

A study in Insect Conservation and Diversity described an experiment performed on pairs of male and female fireflies in an effort to decode fireflies’ mating rituals. The bugs were exposed to five different colours of light, and the researchers recorded the male bug’s light intensity and flash rate and the female’s responsiveness.

The results were dismaying: they showed that all lights, no matter the colour, suppressed mating activity, especially bright amber light, as it matches the color spectrum of firefly bioluminescence.

The solutions to change light pollution can be simple on paper but hard to actually execute. ALAN can not simply be eliminated, and researchers are still trying to find a way to improve the properties of artificial light to make it less disturbing for animals like fireflies.

Fireflies face more challenges besides light pollution; deforestation, harmful pesticides, and climate change are just a few examples.

Sara Lewis, a professor of biology at Tufts University in Massachusetts, told The Guardian, “Fireflies are incredibly attractive insects, perhaps the most beloved of all insects, because they are so conspicuous, so magical. They spark wonder in people. When you are in your back yard or park you notice them and are amazed. They are one of the few things that universally give people a feeling of falling in love in nature.”

Lewis said, “If people want fireflies around in the future, we need to look at this seriously.”