Oakwell Estate’s uncertain future is being saved piece by piece, and the people moving this boulder of a project are high school students.

With construction of Black Rock Middle School’s fields set to begin in May, Lower Merion High School students have been working non-stop to protect Oakwell’s lands.

“Be the change you want to see” is the driving force of our generation – a generation fearful of what our future holds because, for the most part, young adults’ voices are not heard as clearly as adults. Students in Lower Merion Township are passionately working to rewrite this narrative for young adults and empower their local—and even federal—governments.

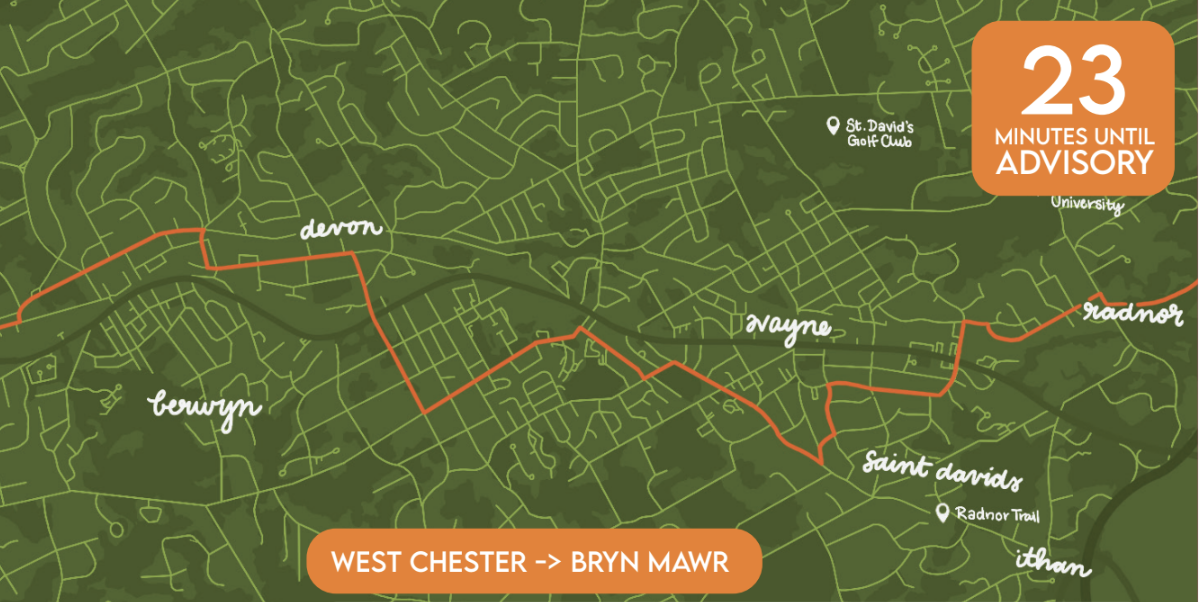

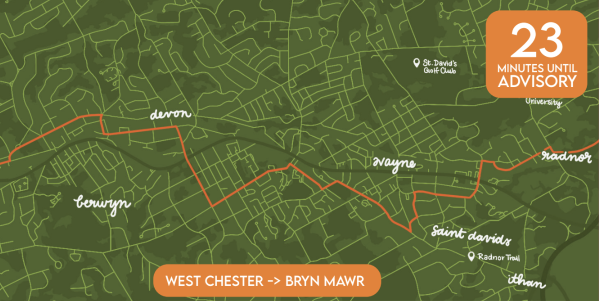

Nestled in the center of the Main Line between Lancaster and Montgomery Avenues at 1835 County Line Road, 13 acres of land, rare plants, century-old trees, and historic buildings sit, flourishing with biodiversity and providing a pleasant sanctuary for wildlife. This slice of heaven is called Oakwell, and it’s currently at risk of being demolished by Lower Merion School District.

Since the beginning of this school year, students have taken the fate of their community and this cherished property to heart, and have been the ones keeping the ball rolling on saving Oakwell from the township’s plan to turn it into flat soccer fields.

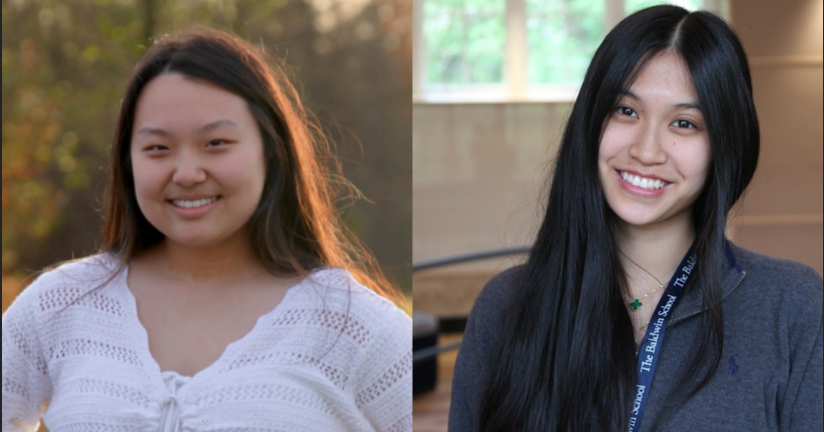

Willa Godfrey, the Vice-President of the Environmental Club at Lower Merion High School, has spent late nights and long hours working to save this historic sight and its lands. Godfrey and I were childhood friends who spent our summers at camp together, rushing to eat popsicles before drops of liquid sugar melted down to our hands—the same hands that would make matching friendship bracelets together in the middle of the camp’s soccer field.

I reflected on that moment when I recently reconnected with Godfrey to talk about the fight she is helping lead for Oakwell. Eight years after first becoming friends on a local high school soccer field, we managed to return to sports fields, but now in the context of protecting Oakwell’s natural lands.

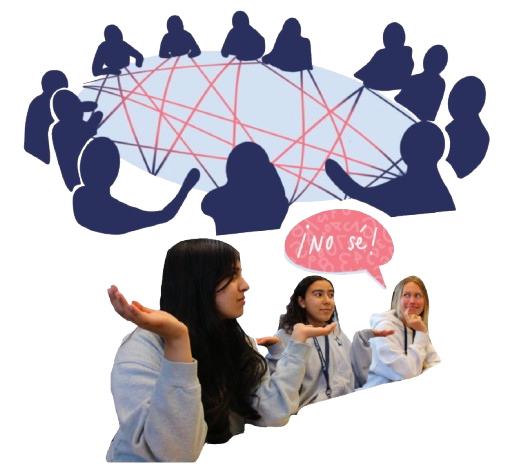

Since I first met her, Godfrey has had a determination to work as hard as she could toward her goals, and it is incredibly evident as she has matured. “Being young, you have a lot more power than you realize,” she told me while sharing the journey of building her confidence while advocating for the causes she believes in. “It’s hard to be 16 and an activist. You get a lot of pushback. It’s a lot of people asking you ‘How do you know what you’re talking about?’”

“I’ve been in a room with 60-plus-year-old men, and I am the only 16-year-old girl in the room. A lot of the time, there’s no one under 30 there. And a lot of the times when I went on tours, all they would say is things like, ‘Wow, you’re so well-spoken for being so young,’ and all I could think is, why do you think that such a young person can’t have well-developed thoughts or articulate them as well as you?” Godfrey told me.

Godfrey and her peers from Grow Oakwell—Sam Donagi, Noa Fohrer, Julia Dubnoff, and herself as student leaders—have been working on the Action Center for Organizing Resilience and Natural Sustainability Education, or the ACORNSE proposal for short: An eight-page proposal about what the future of Oakwell could look like instead of fields – a mecca of interdisciplinary studies. “It’s been a lot of Facetime calls and a lot of time,” Godfrey said.

The students have thought deeply about all the uses of Oakwell and how others can use these spaces to enhance their education, from learning about ecological biodiversity on the property to learning about nutrition and farming and using the area for outdoor theater. The education opportunities the students have thought of are endless.

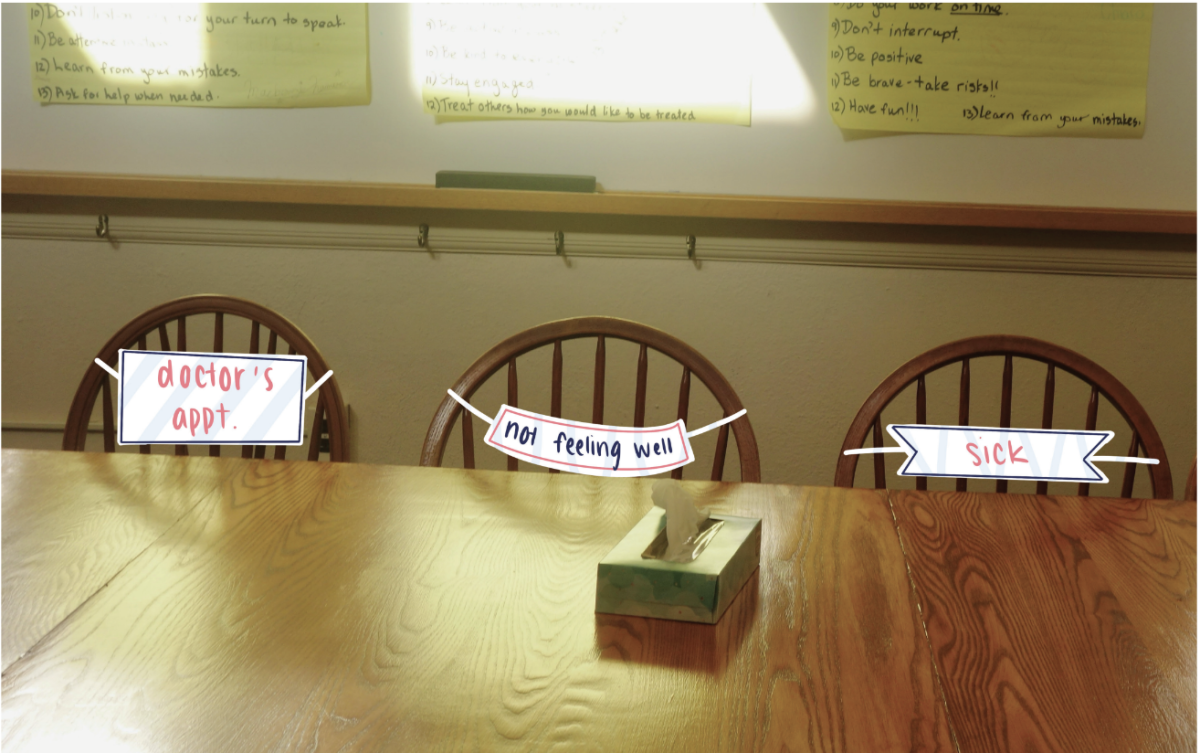

The Enviromental club announced their proposal at a school board meeting back in mid-December, where dozens of students crowded into a meeting room of Lower Merion High School one night, holding up signs that read “Grow Oakwell” and “We want a future” as a handful of students stood to share speeches about why demolishing Oakwell’s lands is not the right decision. The students used their power in this meeting, in ways that moved all, including myself, in attendance.

Students such as Hannah Lowry got up to discuss the biological benefits of Oakwell. She explained, alongside biodiversity specialist Erin Betley, how Lower Merion students have learned that Oakwell’s trees sequester 15 thousand tons of carbon. “Imagine what we could discover with more time,” Lowry said to the Board.

When Godfrey spoke, she raised attention to the fact that Lower Merion could be one of the few schools in the nation with a credible arboretum. “Look around and see what the students want,” Godfrey says while pointing to the crowd of students fighting for Oakwell, “we want to learn.”

Julia Dubnoff, another student leader for Grow Oakwell, also spoke at the meeting with intense and memorable passion.“There are so many ways to incorporate this land into our community, but only one if you tear it down,” Dubnoff said.

This meeting didn’t only showcase the voices of High School students: it also included the voices of students far younger – even as young as 9. Greta Agnew, a future student of Black Rock Middle School, expressed her confusion at the purpose of these soccer fields on Oakwell’s property. “I’m only 9, but it seems obvious to even me that this is not the right option,” she wrote in a letter to the Board that was read aloud during the December meeting.

The meeting was not just moving for attendees, but also for board members. The meeting and the unveiling of the ACORNSE proposal opened new doors for the students fighting for Oakwell: doors to people with power who want to help amplify the students’ voices and their mission.

Because of the proposal that the students shared at the December meeting, Dr. Khalid N. Mumin—who was, at the time, the Superintendent of Lower Merion—approached the students for possible collaborations. Since then, Mumin has been appointed the secretary of Education for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, therefore providing stronger connections and resources in helping the Grow Oakwell campaign.

“Mumin said he would not have thought about an education center (at Oakwell) if it wasn’t for our ACORNSE proposal. It was a very big ‘aha’ moment for us: something we wrote and talked about began to truly impact decisions. It was very satisfying and very validating to hear that our request for curriculum and [an] education center and some hot-spot place for students to learn and soak in all of Oakwell’s beauty was getting positive Board attention.”

As May—the current projected date for when construction of Oakwell is set to begin— looms closer and closer, the Grow Oakwell students are fighting harder than ever. On February 16, the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office deemed Oakwell’s properties eligible for the National Register of Historic Places based on its attachment to Stoneleigh, the older property Oakwell was once part of which is currently registered as Natural Lands. Registry status means that the buildings on Oakwell’s property are untouchable. However, it doesn’t ensure the safety of Oakwell’s immense land and trees. This advancement only enhances the students’ drive for saving Oakwell.

“Right now, we are at the dawn of something really exciting. We feel really excited that we are being listened to more. Along with the National Register of Historic Places, all this stuff that’s paying off is so gratifying when you have been working so hard at it.”

Godfrey encourages students interested in joining the Grow Oakwell project to reach out. “This is a movement for students in general, not just for Lower Merion and Harriton. Students can be listened to if we put our voices out there, but we need more student voices, and within that, we need more student perspectives.”