To Read or Not to Read: Shakespeare In The English Curriculum

Why is English class dominated by a single playwright?

Baldwin upper school students reading one of Shakespeare’s plays for English

Students at Baldwin read at least one Shakespearan play every year, starting in seventh grade. Some students wondered: Does such a large amount of material by one white, English playwright from the 1500s contradict the curriculum’s goal of teaching a diverse range of literature?

Ms. Greco explained that Baldwin does not teach Shakespeare solely because it is tradition. She hopes no department is teaching Shakespeare “just because it’s a classic or because [they’ve] always done it—that argument has no merit.”

Rather, the English department is motivated by specific, pragmatic reasons to share Shakespeare with students, and English Department Chair Dr. Sullivan and English teachers Dr. Forste-Grupp and Ms. Greco shared a few of these arguments.

Ms. Greco explained that the first reason Shakespeare remains valuable is that students will be exposed to Shakespeare in every aspect of their lives. Dr. Forste-Grupp agreed, saying, “A lot of the characters and themes and language have seeped into our collective understanding, so say when you reference a line from Macbeth, everyone knows what you mean.”

Dr. Sullivan added, “Shakespeare sets up the foundation for human psychology in literature.”

Because of the influence of these “cultural touchstones,”’ teachers fear students will not be able to truly appreciate pervasive Shakespearean references if they do not have the opportunity to familiarize themselves with his work in Upper School.

Dr. Forste-Grupp said that if we were to swap Shakespeare for other works, “we would be doing [students] a grave disservice since allusions to Shakespeare characters and plays permeate modern literary texts; lines and characters appear in political writings, the plot narratives become cultural touchstones for writers and philosophers to challenge.”

Another reason behind the emphasis on Shakespeare in classrooms is that the rich literary components in Shakespeare’s plays make them ideal for teaching. Their themes and metaphors help students develop critical thinking skills.

Both Dr. Sullivan and Ms. Greco acknowledged the disparity in the literature that becomes “classic.” They recognized that Shakespeare’s plays are products of their time, and therefore may include anti-Semitic, racist, or misogynistic themes.

When asked how Shakespeare became so influential in the education system, Ms. Greco said, “If we are getting to the nuts and bolts of it, it is likely due to Eurocentric white supremacy.”

However, this doesn’t mean the teaching of Shakespeare need feed into these ideals.

Ms. Greco explained how she “combats the discriminatory aspects of Shakespeare by addressing them in class, rather than ignoring them.”

Dr. Sullivan discussed how, when choosing plays for the curriculum, she “not only takes into account discriminatory language, but also how marginalized characters are portrayed throughout the play’s performance history.”

Dr. Forste-Grupp took a seminar through the Folger Shakespeare Institution the summer of 2021 that offered ways to diversify Shakespeare. She looks for performances and interpretations of Shakespearean works that include more diversity.

Another important factor to consider in the controversy surrounding Shakespeare is that many students enjoy reading Shakespeare, and claim that it’s their favorite part of English class each year.

Carley Taylor ‘23 said, “I think there is a lot of beauty in [Shakespeare’s] language… and I think it’s really interesting how stories have evolved over time.”

Brooke Woo ’25 said, “Part of the reason I enjoy reading Shakespeare is because I can resonate with his writing due to my existing familiarity with the storylines.”

But if students simply like the familiarity of Shakespeare and the experience of performing a play, then would they have the same enjoyable experience if they explored the works of more diverse or contemporary playwrights?

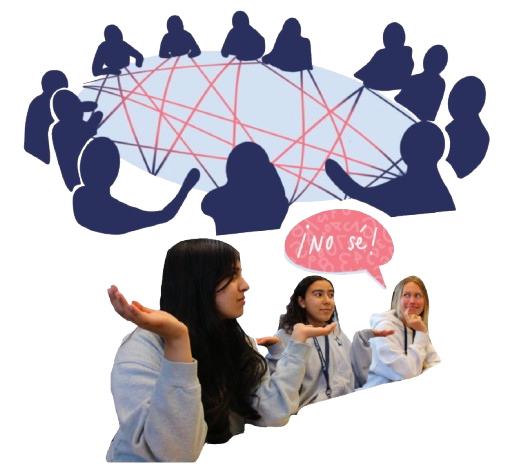

In response, Daria Scharf ‘25 said, “The problem is, we don’t know because we haven’t been exposed to anything besides Shakespeare.”

This returns to an essential question: If Baldwin wants us to have an explorative learning experience, then why are students exposed to such a narrow range of playwrights?

When asked this, Dr. Sullivan pointed out another significant qualification of Shakespeare: the maturity level of his plays tends to suit high school students well. According to Dr. Sullivan, many contemporary plays are “better suited towards a college classroom” since many contain graphic material that could be upsetting for younger audiences.

However, Dr. Sullivan did point out that students have often been assigned more modern plays for summer reading. Some examples she shared are Pygmalion and A Doll’s House.

Additionally, although Shakespeare is at present the only playwright that students read, the broader English curriculum contains significantly more diversity. Works by women and people of color that students read include Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Though Shakespeare remains valuable for many reasons, Ms. Greco said she “[doesn’t] think we need Shakespeare every year” and that there is room to explore whether “Shakespeare can be swapped for more contemporary and diverse playwrights.”

After opening the discussion around the importance of annually reading Shakespeare’s plays, we found a nearly unanimous consensus that there is a great benefit to teaching his work in the classroom, and that exposure to Shakespeare is a crucial part of a student’s academic literary journey. However, there remains controversy as to just how much Shakespeare we need to read, and in what other ways we can push our curriculum forward to include more diverse voices.